‘Classic Vanguard Small Group Swing Sessions’ Review: John Hammond’s Guiding Hand by Will Friedwald

© Copyright ® Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

–“Swing Music was an expression of a new futuristic physics of motion that promised the lean velocity and organic perfection of a bird in flight. What the machine age had wrought in the realm of function, artists were now shaping into a series of self-consciously aerodynamic illusions that implied movement even when standing still. The sleek, legato flow of swing music was an independent but direct extension of that modernistic sensibility into music.” - John McDonough

The producer John Hammond helped bring about the swing era in the 1930s, but a new set highlights the later jazz recordings he oversaw in the 1950s, many of them featuring Count Basie regulars and even the bandleader himself.

Mr. Friedwald writes about music and popular culture for the Journal. He is the 2024 winner of the Jazz Journalists Association Lifetime Achievement award.

The following appeared in the Jan. 2, 2025 Edition of The Wall Street Journal

For order information on Mosaic boxed sets please use this link.

“John Hammond was one of the most important tastemakers and gatekeepers not only in the history of jazz but in the larger arena of American music. His work as a producer, talent scout and general advocate made it possible for such quintessential figures as Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Charlie Christian and Lester Young to have the careers—and the impact—they did. In the latter part of his life, Hammond (1910-1987) moved beyond jazz and was instrumental in the discovery and the early success of Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, Bruce Springsteen and Stevie Ray Vaughan.

His timeline had two peaks: the 1930s, when he helped to bring about the swing era, and the 1960s, when artists he championed brought rock and pop to a new level of maturity. “Classic Vanguard Small Group Swing Sessions,” a new boxed set from Mosaic Records, shows what Hammond was up to between these highest points of his career.

After returning from World War II, Hammond tried working for several independent record labels, but it took him a while to find his footing again. He had grown disenchanted with the latest jazz and was openly hostile to the bebop movement, which, ironically, was at least partly inspired by musicians Hammond had supported, especially Young and Christian.

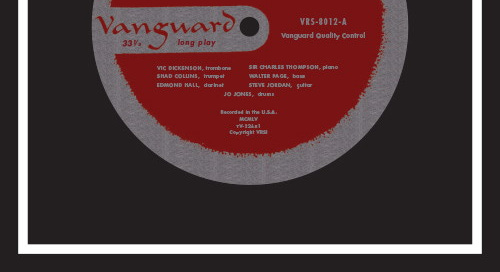

So what kind of music did Hammond produce when given the chance by the Solomon Brothers, who owned Vanguard Records, between 1953 and 1957? He probably regarded these sessions as an updated, expanded and improved version of the music he had produced 20 years earlier. The title to the new box says it all: classic small-group swing. Stylistically, there’s little here that couldn’t have been played in the 1930s. The main difference is the context—it’s performed by more seasoned musicians in a more relaxed setting, with vastly improved audio technology that allowed both more accurate reproduction and a more expansive canvas with longer running times.

The overriding force throughout the eight hours of music is Count Basie; the majority of the leaders here, trombonist Vic Dickenson, drummer Jo Jones, trumpeters Buck Clayton and Joe Newman, as well as the two featured singers, Jimmy Rushing and Joe Williams, were all longtime Basie-ites. The Count himself performs on two sessions and narrates one as well.

The seven discs are filled with swinging riff numbers (such as Buck Clayton’s “Kandee” in a two-trumpet setting with the younger Ruby Braff), blues both fast (Charles Thompson’s “Fore!”) and slow (Joe Newman’s “Blues For Slim”), as well as luxuriously paced ballads. Tenor-saxophone colossus Coleman Hawkins takes top honors in that last department with a stunningly romantic reading of the torch song “It’s the Talk of the Town”—and so does Braff on “Ghost of a Chance,” backed by a choir of horns.

Basie sits in on piano on one song—“Shoe Shine Boy”—on the album “The Jo Jones Special,” led by the most celebrated of the Count’s percussionists. At the time, jazz buffs were excited by the reunion of Basie’s classic “All-American Rhythm Section,” with guitarist Freddie Green and bassist Walter Page, in addition to Basie and Jones. Their ensemble work is as remarkable as ever. But the horns—trumpeter Emmett Berry, trombonist Bennie Green and especially tenor saxophonist Lucky Thompson—attack the music with a fresh and irresistible energy all their own, making this anything but a passive re-creation of the classic 1936 Basie disc, which had also been produced by Hammond.

There’s wonderful playing throughout—and singing as well, especially by Jimmy Rushing, the formidable blues shouter best known for his long collaboration with Basie. Rushing’s three albums for Vanguard—all 24 tracks of which are included here—are a major part of his legacy. Many of these songs are classics that Rushing had previously sung with Basie and others, but the last of the three Rushing albums, 1957’s “If This Ain’t the Blues,” backs Rushing with an ensemble that includes electric organ and guitar and is wholly different from anything else he ever recorded.

The final session here is yet another masterpiece. The 1956 “A Night at Count Basie’s” features the Count as host and guest pianist, backing his current band vocalist, the formidable Joe Williams, on “I Want a Little Girl.” The set was recorded live at the club that the Count owned and operated in Harlem in the mid-1950s. In his excellent liner notes, scholar Thomas Cunniffe quotes Hammond as hating the idea of recording live music in a bar—but, nearly 70 years later, the crowd noises and enthusiasm contribute considerably to the excitement. As if in proof of this, we hear someone laughing loudly over the applause in the final moments of the last track, Vic Dickenson’s feature on “Canadian Sunset.” It is none other than John Hammond, enjoying himself more than anybody, in spite of himself.”

There is, according to Mosaic, a second set of Vanguard recordings to be issued featuring pianists from the same series of sessions.