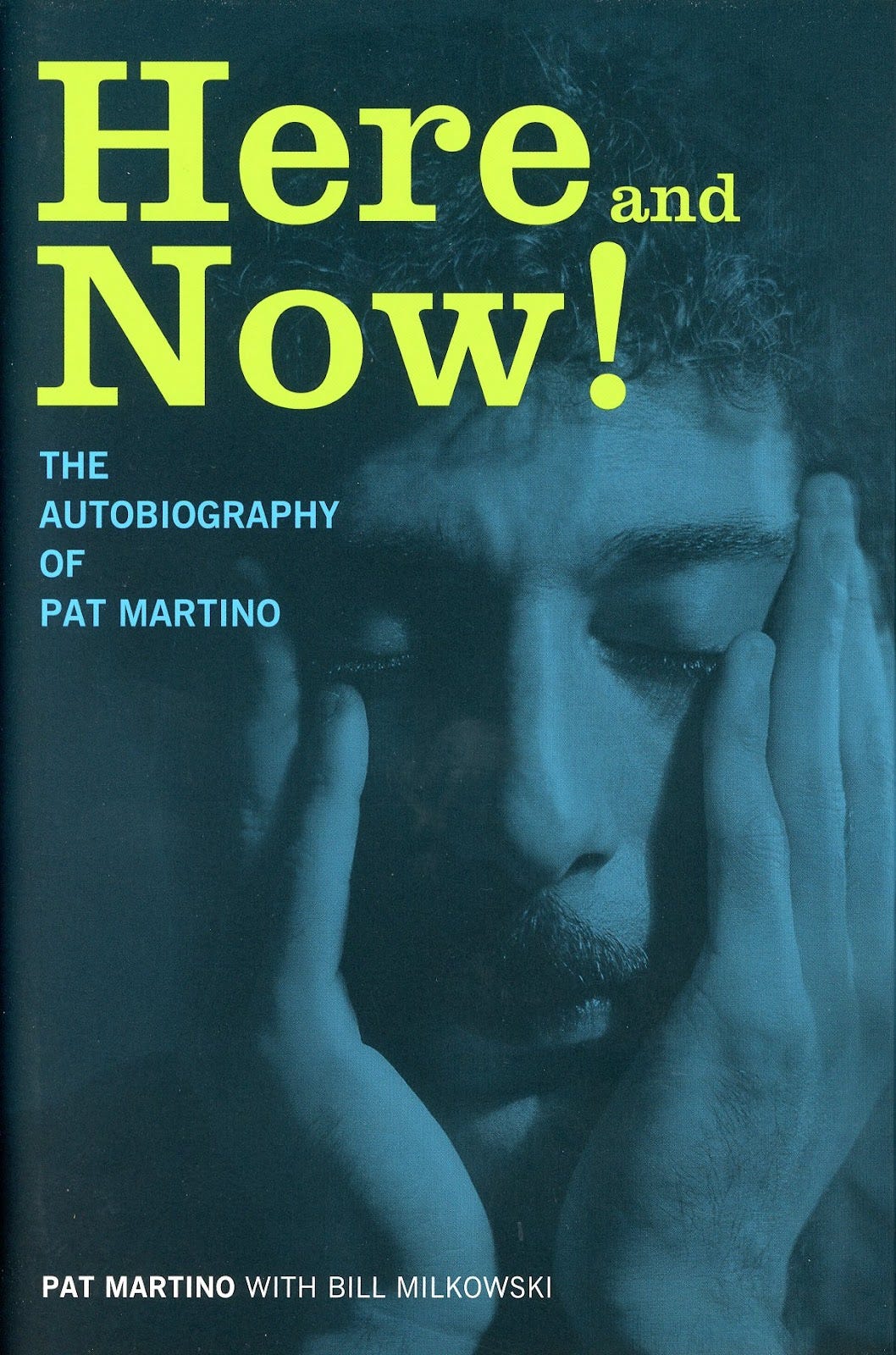

Here and Now! The Autobiography of Pat Martino with Bill Milkowski

© Copyright ® Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Much like Pat - a little guy whose guitar playing packs a powerful punch - Here and Now! The Autobiography of Pat Martino with Bill Milkowski [Backbeat Books, 2011] is a relatively short read that contains loads of information about the music and career of Pat Martino [1944-2021].

The book takes the form of Pat’s story as told by him, commentary by the distinguished author and critic Bill Milkowski and views of Pat’s impact and significance on Jazz guitar from the perspective of other prominent guitarists.

These testimonials from other Jazz guitarists are full of insights into what makes Pat’s playing so unique and so inspiring.

I can’t remember when I’ve enjoyed a book so much. Perhaps it's because reading it reinforced my own views of Pat’s playing and the effect it had on me the first time I heard him on his initial recordings as a leader for Prestige in the late 1960s.

Like everyone else’s first time encountering Pat, I was completely blown away by his rapidly executed phrases which he unrelentingly played with an unerring sense of time and swing. Given everything that was coming out of it, I thought the guitar was going to explode at any minute. His harmonically informed choice of notes and the way he phrased them into a rapid fire attack was unlike anything I had ever heard before coming out of a Jazz guitar.

He made a pick and 6 strings sound like pianist Oscar Peterson’s 88 keys in full flight. How was this possible?

From the perspective of 2011, the details about Pat’s journey as a man and his development into one of the premier guitarists on Jazz history are nicely encapsulated in the Introduction to the book by Bill Milkowski and I thought I’d share it with you “as is” [keeping in mind that Pat left us in 2021]. In it, Bill shares the reactions that many of us in the Jazz World had when we first encountered Pat.

I’ll follow this with some excerpts from the Guitar Player’s Testimony which forms the book’s first Appendix. Another of the work’s Appendices is made up of a complete Discography of Pat’s recordings, samples of which can be found on YouTube for those of you who may be unfamiliar with his work.

© Copyright ® Bill Milkowski, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“This is a story of triumph over incredible adversity. That Pat Martino is still here is astonishing in itself. The man has had so many brushes with death that he stopped counting, a long time ago. That he overcame the debilitating effects of a brain aneurysm and life-saving surgery back in 1980 and ultimately returned to his former glory as one of the greatest jazz guitarists on the planet is nothing short of miraculous. That Pat continues to play, at age sixty-six, with such unparalleled drive and staggering facility, such an unquenchable sense of swing and such heart, is both exhilarating and inspiring to me and hordes of other guitar aficionados all over the world. On a nightly basis, with remarkable regularity, he continues to channel a lifetime of experiences — the bitter and sad along with the joyous and ecstatic — through this tool, this toy, this guitar.

Having always been impressed by Pat's impeccable technique and blazing chops on the instrument, I have come, with the wisdom of advanced age, perhaps, to appreciate his exquisite ballad playing on a much deeper level. Suddenly, his darkly alluring expression on forlorn, melancholic pieces such as Thelonious Monk's '"Round Midnight," Bill Evans's "Blue in Green," or Horace Silver's "Peace" register with greater meaning for me. But he can still burn with the best of them, as he demonstrated recently at Birdland in New York City by surprisingly pulling out John Coltrane's "Impressions," which also happened to be the opening track from his classic 1974 album Consciousness.

It was Consciousness that first pulled me to Pat Martino. I was nineteen years old in that summer of 1974 and back then spent a lot of my free time perusing the bins at Radio Doctor's record shop in downtown Milwaukee, always on the lookout for new jazz guitar albums. I was coming out of a rock phase of worshipping guitar heroes like Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Johnny Winter, and Frank Zappa and was gradually beginning to embrace jazz through such players as Charlie Christian and his direct disciples Herb Ellis, Barney Kessel, and Tiny Grimes. Hearing Joe Pass on Oscar Peterson's 1973 album The Trio (with bassist Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen) was a major revelation, as was his solo guitar album that came out later that year, Virtuoso. I was primed for someone like Pat Martino. And when I spotted Consciousness in the bins, with its striking black-and-white photograph of Pat sitting cross-legged on what appeared to be a lily pad, staring directly back at me with an intense Rasputin-like gaze, I was absolutely transfixed. I took it home, dropped the needle (remember that process?) on the first track — his blazing rendition of Trane's "Impressions" — and was instantly blown away. And I've been a Pat Martino devotee ever since.

When Pat came out with Joyous Lake in the summer of 1977, it fed right into my fusion inclinations (I had been heavily into the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report, and Return to Forever during the early 1970s). Apart from the incredibly powerful music within, there remained a mystical vibe to this extraordinary guitarist, as shown in the depiction of the fifty-eighth hexagram of the I Ching (formed by the doubling of the trigram tui) hovering over his head on the album cover. That particular hexagram not only symbolized the smiling or joyous lake, it stood for perseverance. Little did I know then how much meaning this hexagram would have in Pat's later life.

That fall of 1977, when I heard that Pat would be performing in Madison, about ninety miles away from my hometown of Milwaukee, I made the pilgrimage with my best friend and fellow guitar enthusiast Ric Weinman. Determined to see this mystical six-string guru in the flesh, we drove to Wisconsin's capital city to get enlightened. Pat was appearing in a duo there at an intimate restaurant/club with fellow Philadelphian Bobby Rose, and as we entered the joint after our ninety-minute drive, the two were engaged in a burning rendition of Wes's "Four on Six." We stood in awe of Pat's facility and inventive lines during that set and afterward sought him out for a chat. Surprisingly, he was not only approachable and forthcoming (gods rarely are), he invited us back to his hotel room to continue our conversation. What followed was a rather freewheeling, esoteric rap that lasted into the wee hours and touched upon aspects of guitar as it relates to sacred geometry, twelve-pointed stars, and the sixty-four hexagrams of the I Ching, along with myriad other mind-blowing topics ("Music is food; the guitar is merely a fork") that were way over my head at the time. I left that encounter inspired and determined to elevate my own game as a novice guitar player.

By 1980, after moving to New York, I was already fully immersed in the jazz scene as a freelance scribe. And as both a fan and critic, I watched with amazement as Pat made his heroic comeback following his near-fatal aneurysm — first with an October 12, 1984, performance at the Bottom Line (on a split bill with fellow Philadelphian Stanley Clarke) and then with a weeklong engagement in February 1987 at Fat Tuesday's (documented and released by Muse Records in 1989 as The Return).

My own personal connection with Pat Martino was rekindled some years later when on the afternoon of December 12,1995, I received a phone call from Blue Note Records president Bruce Lundvall. "Bill, lad," he began in that jolly jazz-Santa manner of his, "we just signed Pat Martino and we'd like you to produce his first record with us." Then he laid out a plan for a prospective all-star assemblage of guest guitarists paying homage to Pat, each one appearing on a separate track playing alongside the master. It would be his debut for the prestigious label and usher in a new era of greater visibility for the legendary guitarist, but the overly ambitious project was doomed from jump. Throughout his career, Pat was used to recording whole albums in one or two days with well-rehearsed ensembles. This bloated affair was strung out over a full year and required that Pat create instant chemistry in the studio with musicians whom, in some cases, he had never met before. (Props to co-producer Matt Resnicoff for handling the lion's share of duties throughout that prolonged and often painful process.) It did, however, produce a couple of gems in Pat's delightfully engaging collaboration with Les Paul on "I'm Confessin' (That I Love You)" and his stirring duet with Cassandra Wilson on Joni Mitchell's "Both Sides Now."

Phase three of my interactions with Pat — I guess you could say that my boyhood trip to Madison to see him play back in 1977 and follow up interview was phase one and the Blue Note debacle of 1996-97 was phase two — is this book. In a series of several sit-down sessions at his South Philly home (which bears the unmistakable upbeat signature of his wife, Aya, whose passion for stuffed pigs is apparent throughout the house), Pat revealed insights into his life as well as his philosophy about the nature of life itself.

The narrative arc of the Pat Martino story is epic and compelling, the stuff of legend and Hollywood movies. It's the story of a small, skinny son of a Sicilian laborer in South Philly (family name Azzara) who becomes a guitar prodigy, makes it to the Ted Mack Original Amateur Hour TV show with his rockin' combo at age twelve, then heads out on the road at age fifteen as the only white musician in the eighteen-piece Lloyd Price Orchestra before undergoing important apprenticeships with bandleaders Willis "Gator Tail" Jackson and Jack McDuff in Harlem. By 1967, he joins the band of forward-thinking alto saxophonist John Handy during the Summer of Love, That same year, the twenty-two-year-old phenom cuts his own first recording as a leader, El Hombre (the title itself carries an air of swagger, though the formula doesn't stray too far from his own organ-group roots). And while his early 1968 release East! implies a bit of mystique in the title and the depiction of Buddha on the cover, the program is steeped in hard bop with the occasional foray into more modernist modal territory.

With Pat's next recording, there is a definite stylistic break from his previous outings as a leader. From the cryptic title alone — Baiyina (The Clear Evidence): A Psychedelic Excursion Through the Magical Mysteries of the Koran — it is obvious that Pat is now courting a very different muse on this late-1968 release, one that is more informed by Ravi Shankar and Owsley Stanley than Jack McDuff and the chitlin' circuit. From the mind-blowing cover art to the provocative music within (two guitars executing intricate lines over tabla and tamboura drone, nearly four years before Miles Davis charted this Indo-jazz territory on his groundbreaking 1972 album On the Corner), Baiyina is a daring stretch by a serious artist in transition. In his liner notes, Michael Cuscuna called the work "an astounding suite which signifies a major step for Martino as a player and composer." (Approximately thirty years later, Pat would record a kind of companion piece, Fire Dance, with tabla master Zakir Hussain, flutist Peter Block, and sitarist Habib Khan.)

Pat followed with a string of potent and highly influential recordings through the mid-1970s for the Muse label - 1972's Live! (which yielded a radio-play hit with an instrumental version of Bobby Hebb's "Sunny"), 1974's Consciousness (featuring a blistering "Impressions" and a solo guitar version of Joni Mitchell's "Both Sides Now"), 1976's We'll Be Together Again (his dreamy ballads project with Gil Goldstein on Fender Rhodes electric piano), and the quartet offering Exit — would have a lasting impact on a generation of musicians, and guitar players in particular. That incredibly productive year of 1976 culminated with the recording of Pat's major-label debut on Warner Bros., the adventurous Starbright, and the trailblazing fusion follow-up, Joyous Lake, which was recorded in September and released in early 1977.

And then at the peak of his powers and popularity, the lights went out.

In 1980, following some years of experiencing headaches and occasional seizures, the legendary guitarist suffered a near-fatal brain aneurysm. The emergency surgery that subsequently saved his life left him with total amnesia. As a man without a past — unencumbered by the baggage of history — Pat was now forced to live strictly in the moment, a prospect both horrifying and liberating. He struggled for the next few years through a process of reclaiming memory and gradually reacquainting himself with the instrument he had formerly mastered with such precision and unparalleled facility, until finally reemerging on the scene in 1987 with the aptly titled The Return, a live document of an engagement at Fat Tuesday's in Manhattan. The deaths in fairly close proximity of his mother (in 1989) and father (in 1990) caused an immediate paradigm shift in Pat's world, or, as he reflectively refers to it now, "a time of responsibility and realization." It was during this period when his parents were literally dying before his eyes that Pat privately recorded at home the profound though little-known orchestral work Seven Sketches, which he performed solely on guitar synthesizer triggering symphonic sounds. Included in that collection of works composed between 1987 and 1998 is the darkly dissonant "Mirage," which sounds like it may have been written by Pat as a kind of requiem for his father, Mickey.

Pat got back on a career track in 1994 with Interchange and The Maker and 1996's Night Wings, then rebounded from that aforementioned All Sides Now debacle with a triumphant reunion of his Joyous Lake band on 1998's Stone Blue, which created new visibility for him as a major attraction at jazz festivals and nightclubs all over the world. He followed with 2001's Grammy-nominated Live at Yoshi 's with organist Joey DeFrancesco and drummer Billy Hart (who had appeared on 1976's Exit); 2003's Think Tank with tenor saxophonist Joe Lovano, pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba, bassist Christian McBride, and drummer Lewis Nash; and 2006's popular and acclaimed Remember: A Tribute to Wes Montgomery.

In 2008, British filmmaker Ian Knox released the intriguing documentary Unstrung: A Brain Mystery, which examines the details of Pat's aneurysm, surgery, and struggle to recover his memory, with neuropsychologist Paul Broks acting as an intrepid tour guide. Three very insightful interviews with Pat Knox and Broks regarding this powerful documentary, originally written by Victor L. Schermer for All About Jazz, are included here in the appendix section.

Working as Pat's Boswell on his very revealing autobiography has allowed me to step outside my usual journalist-critic mode and view him not as a guitar hero but as a heroic, inspiring figure. He has defied all odds . . . come back from the dead, so to speak. Back in 1980, he was given two hours to live . . . and he's still here. He has rebounded from multiple surgeries, electroshock treatments, the debilitating effects of COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and a laundry list of other maladies. As his manager Joe Donofrio put it,

I've watched him get in situations that would really defeat most people, and he just bounces out of them. I love his attitude. He's incredibly strong-willed and even at his lowest point he manages to bounce back. I've seen this over and over again with him. That's something he wants people to know about him, and I also think that is something that can help other people. People will call him because they read about his aneurysm and his fight, and he'll talk to them and counsel them. He really wants to be able to help people. He likes to talk to people about how they can get through these tough times.

Donofrio is also quick to point out, "Pat has nurtured his demons in order to understand their pain. And over the years he developed self-discipline. Where once he would explode, he now defuses through self-imposed bouts with reality. In that sense, he became his own guru by conveying a strong spiritual sensibility to his existence."

Pat Martino's story is also much more than a tale of perseverance, just as Pat himself is much more than just a guitar player. Perhaps Kirk Yano, Pat's road manager and engineer since 1998, put it best when he said: "It is a beautiful love story, when you look at the big picture of everything. It's totally about musical love. And you think about all the people that he's touched in five decades ... I mean, it's amazing."

—Bill Milkowski

Guitarist John Abercrombie’s First Encounter with Pat:

“So there we were at this small jazz club in the Roxbury section of Boston called Connolley's, on Tremont Street. It was a very comfortable little club, and all the guitar students hung out there regularly. That night, Pat came on the bandstand, and in those days he was playing a black Les Paul Custom guitar. We knew the guitar was like carrying a Buick on the stage—it was so heavy. And Pat was such a frail little guy. So when we saw this young, very thin little guy walking up to the bandstand with this heavy guitar, I think our first reaction was, "Oh, man, this can't be the guitar player! Who is this? Where's Benson?" He was like a little kid, you know? So we were all chuckling. And then, of course, he started to play and then we ceased chuckling. Because he just floored everybody in the club. I never heard anything like that. I remember they did McDuff’s "Rock Candy," and it burned so hard. And when that band played, it was like the whole club was moving because the band had such a powerful drive and rhythmic feel. It swung so hard, it was infectious. It almost made you wanna dance. It was that kind of thing where the music was really inventive but it could also be danced to, because it was swinging so hard. That was that other element that seems to have disappeared from music. But that original stuff, boy, it was stomping!”

Guitarist John Scofield’s First Impressions of Pat:

“I was in high school, and when I was about sixteen I decided I wanted to learn about jazz and play jazz. So I set myself on the course of study, checking out all the great jazz guitar players. And when I found Pat, it blew me away. He really sounded like jazz to me; his lines sounded just so thoroughly jazz, compared to Coryell and McLaughlin, who had that sort of rock edge. And I loved it. I just wore his records out. First it was his El Hombre and Strings!, his first recordings on Prestige.

Then I went to Berklee, and every few weeks I'd put on one of his records, and I'd be stuck there, listening to it over and over again, just so in love with his playing, just a complete mastery of the instrument in a way that is so special to him. His sound, his chops, his execution, and the evenness of his lines were all so personal. It was a new energy, but he really did sound like such a swinger, the way his eighth-note lines could just burn. I just loved it.”

Guitarist Peter Bernstein On What Makes Pat Martino’s Guitar Stylings Unique:

“Pat Martino is one of the greatest ever to play the guitar. He is instantly recognizable, as everything he plays is completely "him." Like all iconic players, his playing seems to come so naturally from the instrument, yet no one else ever thought to do it that way. His harmonic and linear mastery, as well as his articulation and attack, are what set him apart — he showed you could phrase with the intensity of the horn players that came out of the 1960s. Pat's musical persona is a beautiful and unique blend of ferocity and finesse. He is also one of the great conceptualists of the instrument: infinitely curious about: how physics and mathematics can explain its mysteries. Thank you, Pat Martino, for the infinite inspiration!”

Guitarist Dave Stryker’s Description of Pat’s Impact on His Playing:

“Pat Martino was one of the first guitarists I got into once I got bit by the jazz bug when I was around seventeen (along with Wes Montgomery, Grant Green, George Benson, and Jim Hall). Coming from rock music, I was struck by the fire in Pat's lines. His driving eighth notes and burning approach made me realize that jazz didn't have to be sedate. I remember being blown away by Pat's Live! as I listened over and over (on my eight-track!) driving around in my van during high school. "Sunny" and "The Great Stream" remain classics. I spent many hours taking Pat's solos off his records, and I wore out Consciousness. Later I had to quit listening to his music, as I realized I wanted to have my own sound and there was only one Pat Martino. But I owe a lot to Pat for bringing me into jazz.”

For a heartwarming story about the human spirit prevailing in the face of considerable adversity and going on to create great art, you can’t do better than the story of self-actualization told in Here and Now! The Autobiography of Pat Martino with Bill Milkowski [Backbeat Books, 2011].

All credit to Pat Martino for living it and to Bill Milkowski for telling it so well.