‘Ira Gershwin’ Review: The Rhyme to His Brother’s Rhythm

The lyricist Ira Gershwin outlived his composer brother by more than 40 years, but never quite escaped George’s shadow.

© Introduction Copyright ® Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

Appeared in the December 14, 2024, print edition as 'The Art of the Musical Lyricist'. Copyright ©2024 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Mr. Epstein is an author, most recently, of “Never Say You’ve Had a Lucky Life.”

What Jazz vocalist hasn’t sung “Fascinating Rhythm,” “I Got Rhythm,” “Embraceable You,” or “But Not for Me,” over the years? What brings these melodies to life are their intriguing and interesting-to-sing lyrics. Here’s some background on the lyricist responsible for making these iconic songs a vocal reality.

By Michael Owen Liveright 416 pages.

“So one evening Ira Gershwin and his wife, Lee, have another couple over for drinks, when Mrs. Gershwin suggests they repair to a popular restaurant for dinner. Ira replies that it’s late and that they are unlikely to get a table, but he’ll try. Off he goes into another room where there is a phone, then returns to say that, just as he feared, no tables are available. His friend offers to try. He soon returns to report that, yes, he was able to get a table in the center of the room for 8 p.m. “How did you manage that?” Ira asks him. “Simple,” the friend replies. “I told them I was Ira Gershwin.”

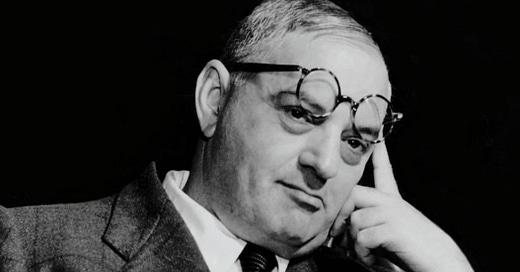

This anecdote does not appear in Michael Owen’s biography of Ira Gershwin. But the tale, frequently shared by the writer Arthur Kober, is a story about modesty. Ira Gershwin learned his modesty at home. Born in 1896 as Israel Gershovitz, the first child of immigrant but not religious Russian-Jewish parents, Ira was soon overshadowed by his two-years-younger brother, George, who was more confident, more self-assertive, vastly more talented. The Gershwins’ mother, Rose, favored George; their father, Morris, was too busy failing at various businesses—pool halls, cigar stores, bakeries—to devote much time to any of his four children.

George Gershwin meanwhile, precocious in everything—he was able to play piano before he had had a lesson—left school at 15 to work plugging vaudeville songs for a music publisher, while Ira worked at a number of futureless jobs, among them handing out towels at a Turkish bath in Coney Island in which his father had a financial interest. Ira—small, overweight, needing glasses, not much of a student—developed a gift for language, a gift encouraged by his brother George, that he would soon put to use in his work writing the words for other men’s music.

“Lyricology,” as Michael Owen notes in his biography, is not an established subject, which is to say that not all that much is known about the lyricist and his work. Many popular composers—Irving Berlin, Cole Porter, Stephen Sondheim—were able to do without lyricists, writing both music and lyrics themselves. Others—Jerome Kern, Richard Rodgers, George Gershwin—found lyricists indispensable. The construction of lyrics is fraught with complications. Some composers could not write their music until they had the lyrics before them; others—George Gershwin again—wrote the music and let lyricists find words to fit the music.

The lyrics of the songs of what came to be known as musical comedy—featuring romance, colloquial speech, street slang—may indeed be the true American poetry. They were written by, among others, Yip Harburg, P.G. Wodehouse, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and Ira Gershwin. As for the job of lyricist, it is perhaps best described by Ira Gershwin himself: “Given a fondness for music, a feeling for rhyme, a sense of whimsy and humor, an eye for the balanced sentence, an ear for the current phrase and the ability to imagine oneself as a performer trying to put over the number in progress—given all this, I would still say it takes four or five years collaborating with knowledgeable composers to become a well-rounded lyricist.”

On the precariousness of the lyricist’s job, Ira wrote that it requires “a certain dexterity with words and a feeling for music. . . the infinite patience of the gemsetter, compatibility with the composer and an understanding of the various personalities in a cast.” Difficulties invariably arise. Songs one loves are canceled from shows, some performers insist on alterations in what one has written, others perform them poorly, the whims of producers are weighed, disputes over royalties emerge, entire shows are closed down for want of public taste.

The reader comes away from Mr. Owen’s “Ira Gershwin: A Life in Words” with a strong appreciation for all that the craft of the lyricist entails. (One is all the more impressed with the accuracy of the author’s subtitle when one learns that Ira Gershwin could not read music.) More important, at the close of Mr. Owen’s biography one feels that one knows Ira Gershwin—knows him and likes him. In these pages we learn what the world thought of Ira Gershwin, what his co-workers and family thought of him, and, through Mr. Owen’s careful mining of his subject’s letters and diaries and pronouncements, what he thought of himself.

Ira Gershwin understood that he was himself a secondary character. He was secondary above all to his brother George. At the center of Ira Gershwin’s life was his immensely talented brother, who, at the age of 21, wrote “Swanee,” lyrics by Irving Caesar, sung by Al Jolson, an immediate and enduring hit. George Gershwin would later compose “Rhapsody in Blue,” which mixed classical music with the spirit of jazz. Later, when the Gershwin brothers teamed up to write the musical “Lady, Be Good!” “the American musical theater,” in the words of Philip Furia, in his “Ira Gershwin: The Art of the Lyricist,” “finally found its native idiom.”

The Gershwin brothers’ songs—“Fascinating Rhythm,” “I Got Rhythm,” “Embraceable You,” “But Not for Me,” “Bidin’ My Time,” et al.—in Philip Furia’s words, “reveal Ira’s complete mastery at balancing simple and comic lyrics, infusing popular-song formulas with light-verse flourishes, making his wit perfectly singable and avoiding both flippancy and sentimentality as he registered genuine feeling.” George Gershwin’s songs were never better than when Ira supplied their lyrics.

George’s death, in 1937, at the age of 38, owing to a malignant glioblastoma, was a staggering blow to Ira, who never really got over it. (Mozart died at 35, Chopin at 39, Bizet at 36, Mendelssohn at 38—the early death of great composers is an all-too-frequent occurrence.) Ira would outlive George by 4½ decades, a fair amount of them devoted to preserving his brother’s achievement. Earlier, in 1933, when the musical “Of Thee I Sing” won a Pulitzer Prize, Morrie Ryskin, George S. Kaufman and Ira were the announced prizewinners, but not George Gershwin, for Pulitzers in those days were not given for music. Ira was much aggrieved at the unfairness of his brother’s exclusion.

After his brother’s death, Ira would work with Moss Hart, Kurt Weill and others—he wrote the coda for Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg’s “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”: “If happy little bluebirds fly / beyond the rainbow / why, oh why, can’t I?” But more often he brought an impressive sophistication to his lyrics, the product of his wide reading. In “How Long Has This Been Going On?” we find “I was kissed / by my sist- / ers, my cousins, and my aunties. / Sad to tell, / it was hell / an inferno worse than Dante’s.” In George’s and his “A Foggy Day,” you will recall “I viewed the morning with alarm. / The British Museum had lost its charm.” The ballad “But Not for Me” contains, “With Love to Lead the Way, / I’ve found more Clouds of Gray / Than any Russian play / Could guarantee.” And from “Isn’t It a Pity?” we find mention of Heine and “My nights were sour / Spent with Schopenhauer.” Difficult to imagine any of Gershwin’s contemporaries, apart perhaps from Cole Porter, availing him- or herself of such rich literary references.

Grow though his fame did over the years, Ira Gershwin remained, in Michael Owen’s words, “a reluctant celebrity.” He found the leisurely life of California, which he discovered when he and George set out to write for the movies, preferable to that of the raucous tumult of New York. He dabbled in leftist politics, led by his wife, who was more political than he, and in many ways his opposite in her lively temperament. He had an immense success with “Lady in the Dark,” directed by Moss Hart, music by Kurt Weill, with a starring role for Gertrude Lawrence. He regularly edited his own earlier lyrics. He foraged in his brother’s notebook—“tunebook” George called it—for further tunes for which he might supply the words. But, as he neared 60, as Mr. Owen notes, “he was at a creative crossroads: three years of writing songs for the movies had proved professionally unsatisfying,” and Broadway, in Ira’s view, seemed less than promising.

He published a book, “Lyrics on Several Occasions” (1959), which did not find commercial success. He stood guard over his brother’s reputation. When an exhibition about the Gershwins was staged at the music division of the Museum of the City of New York, Ira joked that the true title for the exhibition ought to be “Principally George (and Incidentally Ira).” He spent much time sorting through the financial details of the distribution of the royalties from his brother’s and his music and later his mother’s will, so much that he claimed he had become “really a bookkeeper.” If any criticism can be made of Mr. Owen’s excellent biography, it is an overload of financial details, rendering the book, at moments, best read by a CPA.

Old age kicked in for Ira Gershwin, with its various ailments and, in his case, many falls, resulting in broken ribs and other injuries; he referred to these latter as “rhapsody in bruise.” He died peacefully, of a heart attack in his sleep, on Aug. 17, 1983, at the age of 86. We do not know what Ira Gershwin’s last words might have been, but one likes to think that they were both rhymed and singable.”

Beautiful. 😍