Jazz Vignette #3 - Gunther Schuller on George Russell and Bill Evans

A Tribute to Gunther Schuller.

© Introduction Copyright ® Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“How things have changed! Dare I say advanced and improved? When these eight compositions were recorded and first performed about 40 years ago, the average record listener and buyer, and ever most critics, considered them (at worst) "incomprehensible," "anti-jazz," even "anti-music," "absurdly avant-garde," "beyond the pale," or (at best) "controversial," "difficult," "abstract," "unrewarding."

The world of music in the 1950s was still for the most part divided among sharply defined lines of musicians who, on the jazz side, could not (or preferred not to) read music—and then only of the simplest and most jazz-conventional kind—and also could not improvise on anything but traditional tonal "changes;" while on the "classical" side musicians could not improvise, could not swing, could barely capture the unique rhythmic inflections and expanded sonorities of jazz.

Today those erstwhile separate worlds have come together, have cross-fertilized, in variously overlapping ways, and learned much from each other. A rare pioneer on the frontiers of jazz, such as Scott LaFaro, Bill Evans, Eric Dolphy, who in those days had both the "chops" and the ears to deal with these new musical fusions, has been replaced by a whole generation of younger performing and creative talents, for whom those old stylistic and conceptual boundaries have long since disappeared.

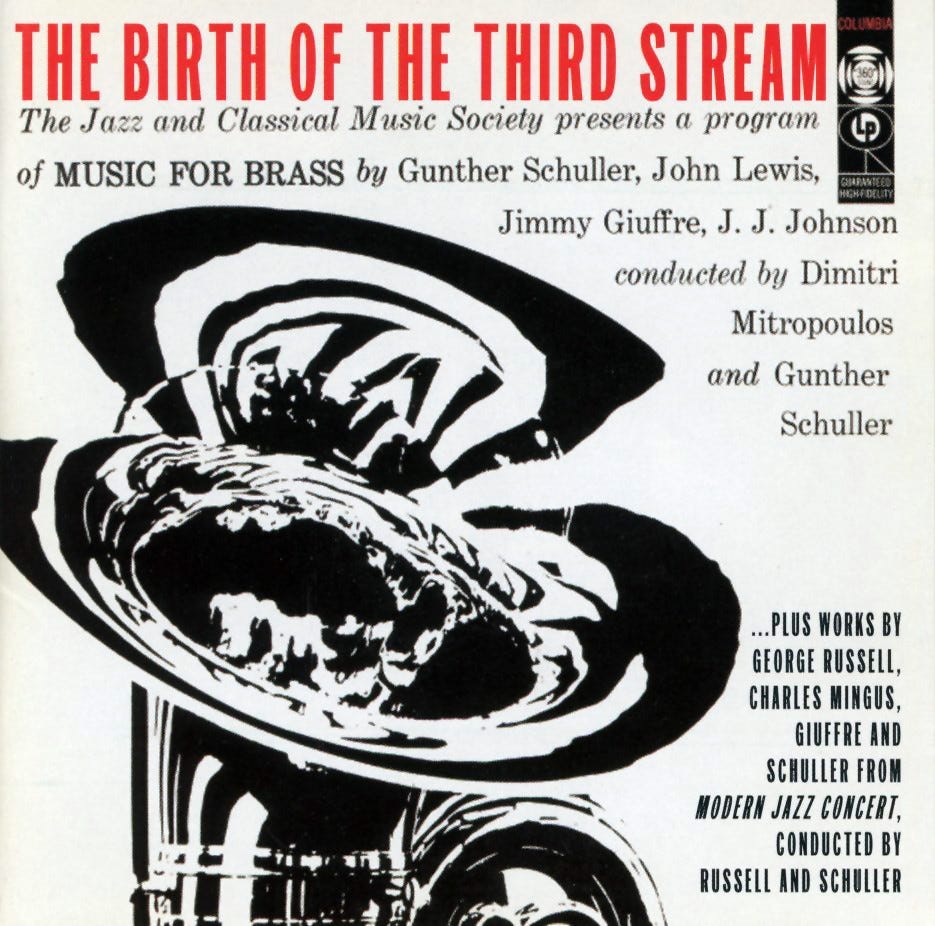

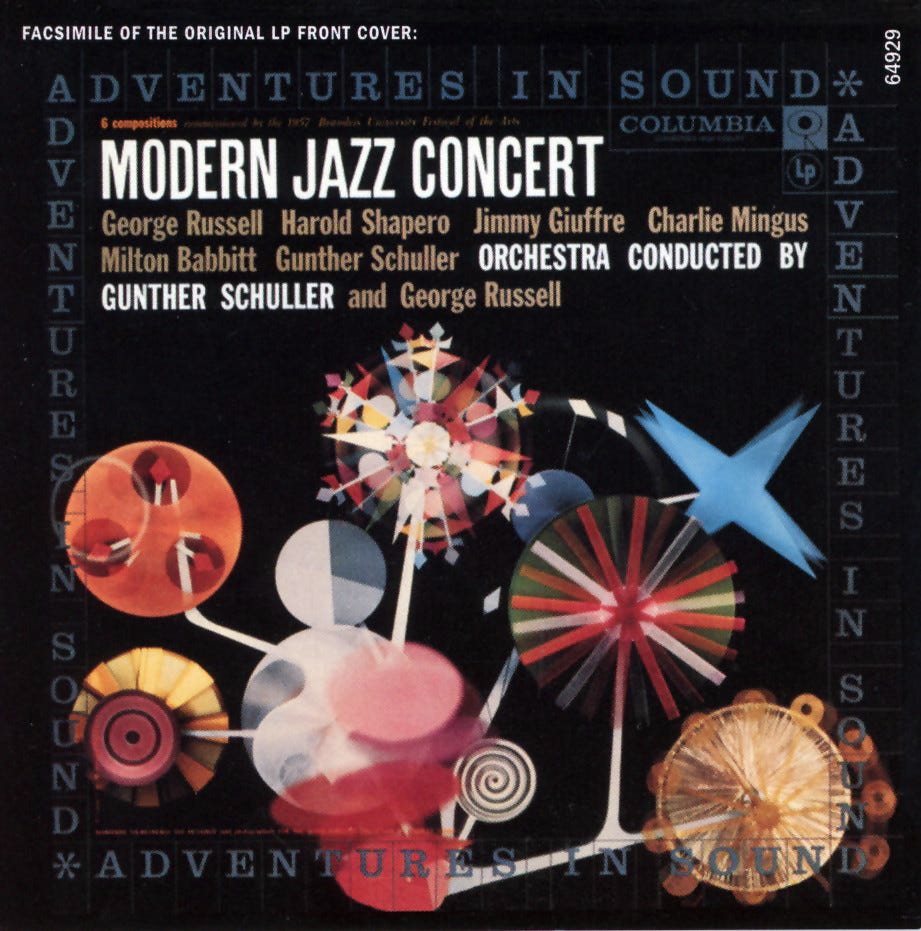

GUNTHER SCHULLER CONTINUES WITH HIS 1996 REMINISCENCES from the insert notes to The Birth of the Third Stream: The Jazz and Classical Music Society Presents a Program of Music for Brass [Columbia/Legacy CK 64929]

Before Bill Evans became a Jazz artist with a national and ultimately an international following, he caused quite a stir in the New York Jazz community of the mid- 1950s.

This was largely thanks to the composer, arranger and bandleader George Russell who was also just then making a name for himself in similar circles.

The confluence of events centered around two extended compositions by George that featured Bill. The first occurred in 1956 on Russell’s Concerto for Billy the Kid [which according to George, “attempts to supply a framework to match the vigor and vitality in the playing of pianist Bill Evans’]; the second in 1957 on his All About Rosie.

As described in the following excerpts from Duncan Henning excellent biography - George Russell The Story of an American Composer [2010], there was a personal dimension to the relationship between George and Bill that led to a burgeoning professional one:

“Evans would prove to be one of two musicians, significant in themselves in jazz history, whose names would be forever associated with Russell. The other is Jan Garbarek, the Norwegian saxophonist.

Russell had met Evans through Lucy Reed, a singer he had known in Chicago and perhaps had a relationship with. Reed was working in New York with Evans as her accompanist, at that time a role low on the food chain for a jazz musician. As Juanita Giuffre [George and she were married in the 1950s] explains,

‘Oh, Bill was a dear friend. He really was. He was a sweetheart and he looked like a minister's son. When we first met him, we went out on a ferry ride with a girl who had very much a big crush on George, but she brought Bill Evans anyway, and we went out on this ferry thing around New York City and Billy's standing there by the rail looking very studious and anything but a jazz musician, and this girl was saying, "He plays very well and he's quite a nice piano player"—-because he at that time was accompanying her, which to us was just like accompanying—we didn't think much of it.’

Russell's own recollection of the experience continues:

‘A singer who lived in Chicago knew me—a very sweet singer—and she brought Bill up to the 24th Street hang where Juanita and I first lived in the one room. There wasn't anything to do on Sunday in New York, it was summertime and New York is like a desert. So she introduced me to her friend, and he seemed very detached like a businessman, like he belonged to a bank, worked in a bank. He didn't seem to be very joyful. So I said in desperation, "Let's take the Staten Island Ferry," which we did, carne back, and Lucy said, "This man's a piano player, Ask him to play." That's one thing we had in the place—a piano. "Yeah, why don't we ask him to play. Why not, you know?" Expecting to hear a bank teller doodle on the piano, (whistles) It was one of those times when you feel like you're being blown up in witnessing a very special kind of adventure, as he played piano like nobody I ever heard. I didn't expect that outta him. And that self-reserve thing, you could see in his music there was much more to him. He and I became very good friends. I got him onto Victor. I wouldn't have anybody else. I knew who I wanted to play piano on the Victor album. [George Russell - The Jazz Workshop].’

Evans could evoke that kind of shock and awe despite his quiet and unassuming appearance, and could do so without resorting to grandstanding or pyrotechnics. Pianist Jack Reilly, who later studied with both Russell and Lennie Tristano, first met Evans in the early fifties.

‘I was at the Navy School of Music in Washington, D.C. I heard this piano playing coming from this room and I said, "What is that?" This guy said, "It's Bill." Shearing, Teddy Wilson, Bud Powell—everything but with a notch above, and a synthesis already in his playing of all three. I said, "Oh my god," Such fluency. I got to play with him. Then, of course, I got all his recordings; I got all the ones with George especially.’”

The distinguished Jazz historian, composer arranger Gunther Schuller puts the entire association between George in Bill in a larger context in his sleeve notes to The Birth of the Third Stream a Columbia CD that combines two LPs - Music for Brass [1956] and Modern Jazz Concert [1957] which contains All About Rosie.

By way of recommendation, if you have any interest in gaining an understanding of what was involved in the relatively short-lived Third Stream [Classical is one stream; Jazz is a second; a combination of Classical + Jazz forms the third] Movement, in addition to the comprehensive representation of this style of music contained in its eight tracks, the informed and instructive booklet notes will prove invaluable.

FROM THE ORIGINAL NOTES BY GUNTHER SCHULLER (FOR MODERN JAZZ CONCERT, 1957)

“As recently as ten years ago, this album could not have been produced, either in terms of performance or in terms of the marketability of its contents.

But so rapid has been the progressive intermingling of influences in the jazz and non jazz fields that there exists now a nucleus of musicians—albeit still limited in number—who can combine the ability to read "far out" twelve-tone scores with that prime requisite, the life-force of jazz? improvisation. (This should not be confused with the ubiquitous manifestation known as "commercial music" which, while it demands of the musician the ability to read and even occasionally challenges him to improvise, does so on a cliché level that suppresses creative imagination by the stereotyped mass-appeal patterns that it explicitly sets out to achieve.)

Music such as recorded here, of course, will once more bring up the often-raised questions. But is this still jazz, and is this intermarriage of two separate kinds of music valid?

In the short space available here, it is perhaps not possible to discuss conclusively such a thorny question— if this he possible at all—mainly because people in general, and jazz aficionados in particular, seem to have an irrepressible urge to pigeonhole their favorites into neat little category packages. And thus such and such is jazz, such and such is not. (We all know the purist to whom anything after 1925 is no longer jazz, or the latter-day jazz protagonist who thinks anything left of center—center at present being Sonny Rollins, Horace Silver, et al—is also outside the realm of jazz.) It just so happens, however, that creative musicians since the beginning of music — not to speak only of jazz — have never concerned themselves too much about what their product would be called or whether it would fit certain established categories.

The truly creative artist has always — to the extent of his talents and artistic sincerity — followed the demands of his creative personality, and it has been the job of the historian and theoretician to explain and categorize artistic events after they occurred. (To cite only one very simple but pertinent example, the music now called "jazz" was played for years before it was known as such; arguments as to when it was first called jazz and why are still in full swing.)

As a matter of fact, the entire history of the arts was, and still is, precipitated by precisely those glorious moments in which the innovator of genius defies the established patterns and rules, thereby opening up new vistas for him and others to develop until the next big breakthrough occurs. The music lover of all periods, and also the record buyer of today, has a long history of resistance to these innovations of the great masters of past and present; and this is his right and privilege. We hope, however, that he will not find it necessary to exercise this right in regard to this album.

At any rate, perhaps this is jazz or perhaps it is not. Perhaps it is a new kind of music not yet named, which became possible only in America where, concurrent with a rapidly growing musical maturing, a brand new musico-cultural manifestation came into being, which has by now spread to all corners of the earth. Perhaps right now Japanese musicians, for instance, are working on a synthesis of jazz and their own ancient musical traditions [Twenty years later Toshiko Akiyoshi did something like this when she combined Jazz cultural influence into her bi band arrangements.].

For who knows what the influence of jazz on other cultures as well as our own will produce in years to come? Speaking for myself, I can only say that the possibilities seem to me both exciting and limitless, and it seems irrelevant to worry about whether this will be jazz or not. It does seem relevant to worry about whether it is musically valid and meaningful within the time and society that produce it.

On this basic premise I will therefore not categorize and typecast the six works on this record. In view of the newness of much of the music, this would seem premature, and might in the process re-nourish prejudices which could limit the listener's enjoyment. Instead, I should like to give the listener the all-too-rare opportunity of uninhibitedly roaming over the wide range of personalities and concepts displayed here. For it was one of the marks of success of this Brandeis concert that the six works commissioned by the University not only were of high quality but as different in their immediate concepts as is possible to envision, while yet all—in a general way—subscribing to the same point of view. I will therefore limit myself to a few remarks about the works, remarks of an essentially noncategorical nature, that will aid the listener in appreciating some of the more salient moments on this record, both in terms of playing and writing.

"All About Rosie" by George Russell, is based — to quote the composer —"on a motif taken from an Alabama Negro children's song-game entitled 'Rosie, Little Rosie.'"

The work is in three movements. In the first, a fast pace is set by the trumpet. Alternating between sections in 2/2 and 3/2 meter, the composer builds a gradually mounting tension through excellent manipulation of sequences and repetitions, culminating in a sudden climactic ending.

The second movement changes the mood; it is slow and has a distinct blues feeling. Notice how the composer at first effectively avoids establishing a specific tonality. Only gradually do the several lines in the flute, bassoon, tenor, etc., coalesce into a definite tonal picture, a process quite indigenous to George Russell's own particular modal concept, which effectively encompasses everything from pure diatonic writing to extreme chromaticism. Especially striking in this movement is the guitar writing, superbly played by Barry Galbraith. Again a climax is built with the two trumpets in unison over a rich ensemble. There is a sudden relaxation, and on a short questioning note the movement ends much as it began.

In the third section, the fast relentless pace of the opening is resumed, with the element of improvisation added. Outstanding in this respect is Bill Evans' remarkable piano solo. The ideas are imaginative and well related, but — more than that — Bill's strong, muscular, blues-based playing here fits dramatically into the composition as a whole. [Bill’s solo begins at 1.18 minutes] Other solos (La Porta, Farmer, Charles, McKusick), and a recapitulation of the opening statement, lead to a brilliant ending.”