Introduction © Copyright ® Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

There’s too few quotations by Larry in this downbeat interview for a standalone piece, and that coupled with the fact that all interview material with Larry is at a premium helps explains why I am using these quotations from Larry’s participation in Harvey Siders article Drum Schticks from the March 15, 1973 Downbeat as lead-ins to Mal Sands piece Whatever Happened to Larry Bunker? from the May 1994 edition of The LA Jazz Scene.

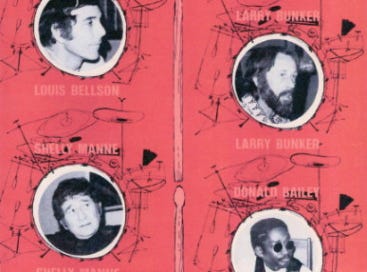

Other participants in Harvey’s interview besides Larry were drummer Shelly Manne, Louie Bellson, Willie Bobo and Donald Bailey.

As always Larry demonstrates once again how much thought he put into his playing and the remarkable ability he has for clearly and forcefully articulating his opinions about Jazz drumming in particular, and music in general.

DRUM SHTICKS By Harvey Siders

DownBeat: I'd like to start off with a statement, not a question: I don't like long drum solos. They bore me. (Long, uneasy silence. Did I blow it at the very outset?)

Larry Bunker: There was an interesting point in Harvey's question —about losing your place after three choruses. Now there are some guys who, once you say "Okay, you got it," just start to play with no relationship to the song form or the construction o! the tune. Drum solos like that do not often appeal to me. And I never play solos like that. When I solo I always think in terms of the structure of the tune, and I play choruses. I will invariably lose the guys in the band, but I will know where I am.

DB: You think in terms of first 8, second 8, release, etc.?

Bunker: I always think of 4-bar phrases and 8-bar phrases. I may turn it around and go into odd things, cross the bar lines, and Lord knows what, and arrive at what would be important accents in places that are not important accents. But that's how I'm constructing it. The band may think that I've made a mistake. They don't have the additional framework to hear it against. It's like pianist Russ Freeman. He could play three choruses out of time and finally the whole rhythm section would give up and go with him and he'd say: "Why did you do that? I didn't turn the time around."

Manne: That's right he [Russ] always knew where he was.

Bunker: Now if you're asking about playing with Miles' band, then it's freak-out time: no bar lines, no meter, not even a center of tonality, and everybody's hung out here in space. That's another thing.

DB: I don't know about that. Last September at Monterey, I heard Rollins, in the middle of his set, dispense with his rhythm section and go into a long, unaccompanied solo that was beautiful, swinging, and never without a frame of reference.

Bunker: There's another consideration. The saxophonist - especially if he's a Sonny Rollins — can do that because he has about 30 notes available to him on the range of his instrument; maybe more, if he goes into harmonics. So he has not only rhythmic variations, but melodic variations, and can imply harmonic construction. The drummer has five or six or seven tones available to him, and the colors of his cymbals, and that depends on how complicated a set of drums he's using. So the scope of what he has to work with is greatly diminished, and he has to function mostly with rhythmic values and permutations of those rhythmic values, and there's not that much tone or pitch value that he can bring into his solos.

DB: Turning to a different kind of sound, has today's jazz drummer learned anything from rock, or is it a completely one-way street where rock drummers are the ones who learn from jazz drummers?

Bunker: There's one element that has come out of rock that should prove useful to jazzmen, if they pay attention. A lot of people have criticized rock as being too simplistic. And in many ways it is. Most jazz musicians are capable of going through mental gymnastics. When you consider what people like Bird and Sonny and Bill Evans can do in terms of improvisation, it becomes mind-boggling. Especially when you think of what is involved not only the mastery of their instruments, but their mental chops. Well, the music of jazz has become so complex that a lot of times they forget all about swing. One thing that many rock players do is cook like sons of bitches. The good ones get a groove going that many jazz players have overlooked. Sure. Their music is simpler. but so was a lot of the swing music of early jazz. Less sophisticated, but it gave jazz players time to breathe, time to think about things like time and the groove and that's what a lot of rock players are doing. Their music is not as intellectually stimulating, but often I find it more satisfying than what some jazz musicians are doing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to CerraJazz Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.