© Copyright ® Steven Cerra, copyright protected; all rights reserved.

“If there are four pictures and I’m smiling on two, they pick the one with the serious look.”

“People tend to pigeonhole everything. My image seems to be of the intellectual, serious, romantic, lyric, ballad player and this is certainly one side of myself. But I think I put much more effort, study and development and intensity into just straight ahead jazz playing, the language of it and all that — swinging, energy, whatever. It seems that people don’t dwell on that aspect of my playing very much; it’s almost always the romantic, lyric thing, which is fine, but I really like to think of myself as a more total jazz player than that.”

“The music is moving. Inside of itself it's moving and it's fresh and developing in a way I haven't felt since that very first trio.''

“It's encouraging—the audiences are getting larger and they're mostly young people. Eighty percent of our audiences are young people that ten years ago wouldn't have been aware of jazz at all."

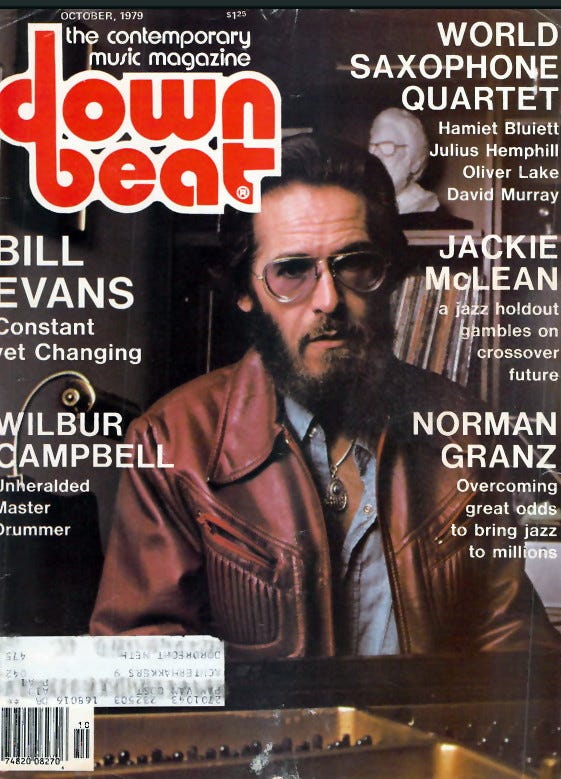

Bill Evans

The following appears in the October 16, 1979 issue of Downbeat. Despite its tone of vitality, Bill would be dead less than a year later [he died on 9.15.1980]. Les may have inferred the reason for the onset of Bill’s demise when he writes - As Bill Evans speaks his eyes dart around the floor. He is thinner than he has been and his beard looks a little longer. It’s fairly common knowledge that Bill was once again using drugs, this time with a preference for speedballs - a concoction of cocaine and heroin.

© Copyright ® Lee Jeske copyright protected, all rights reserved, and is used with the author’s permission.

“I think I’m more satisfied to be myself now than ever before. You know in the Bible it says you change every seven years and I’ve gone back and looked at that in my life and I can see, within a year on either side, where major changes have taken place. I’m 50 now, so that's the beginning of a new period according to the seven year cycle. I guess maybe the 50th year is rather sobering. Forty was kind of sobering, but I think 50 maybe, in a different way, marks something important. Forty makes you realize you’re not a kid anymore. Fifty is more of a placid kind of mark, where you feel more tranquil and realize that you are getting on. You can relax with yourself more and not worry about trends or anything else, which have never affected me that much. But it's completely out of mind now.”

Bill Evans sits on the edge of the couch in his Fort Lee, New Jersey, apartment, sipping a banana, ice cream and egg concoction nestled in his large, puffy hand. In the 25 years that he has been an active musician, Bill Evans has remained one of the busiest and most influential of all jazz pianists. He has never been out of work and figures he has been responsible for some 50 albums. Eleven of those years, from 1966-1977, were in collaboration with bassist Eddie Gomez. Gomez’s leaving coincided with the departure of drummer Eliot Zigmund, a two year member of the trio.

“It certainly was traumatic going through the changes after Eddie left and, of course, losing a drummer, too, who was established into the group and into the music. Philly Joe Jones came in for a year and I must have used four or five different bass players — more or less searching and also giving these bass players a chance to try the music and decide whether they wanted to make a commitment. There are many, many qualities which have to manifest themselves. The main thing I would think of would be potential for growth within the music and a stimulating attitude. Something that you can’t quite put your finger on verbally.

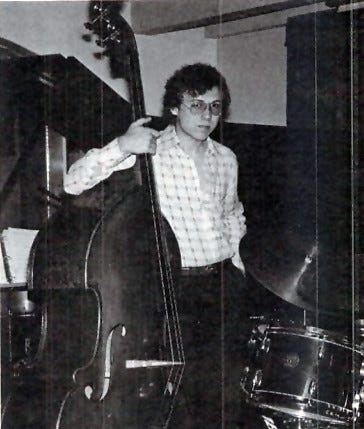

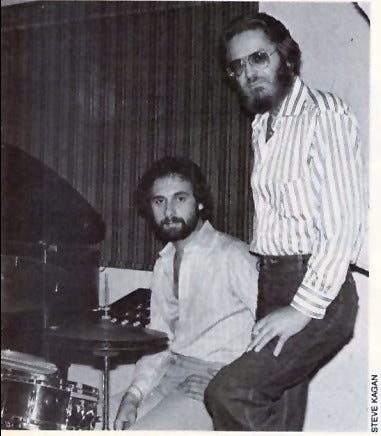

“Marc Johnson was touring with Woody Herman at the time and had been calling me. He was playing West Virginia with Woody and had a day off, so he flew up to the Vanguard with his bass just to sit in. I knew very quickly, musically, that Marc was the guy I was looking for and it certainly has proved out. He’s developing at a fantastic rate and just wasting the people.”

Gomez left on amicable terms. “Enough of one thing is probably what it amounted to. I really would have expected it sooner. I'm certainly glad that he didn’t leave too quickly; we got a million things together and he’s a fantastic player.”

Drummer Joe La Barbera rounds out the current group and Evans is delighted. “I feel like all that trauma of about a year looking for the trio that I finally ended up with was probably one of those necessary transitional things that allows you to arrive at something which is special. Marc is exciting me and Joe, and Joe is exciting Marc and I, and we’re really having a marvelous time.”

There seems to have been a new Bill Evans developing over the past few years. The quiet, introspective musician of a decade ago has become somewhat jauntier and more aggressive and his stage manner has become looser. Much of this is attributable to Bill’s personal life and his marriage of six years.

“Yeah. I have a family, a young son and a 12 year old stepdaughter, and that probably has something to do with it. Part of it is that I’m at a certain period in my life where I’m coming into a good period of creativity and, I don’t know, just a freshness. The trio is certainly somewhat responsible. But it also has to do with the time in my life. The music is moving. Inside of itself it's moving and it’s fresh and developing in a way I haven’t felt since that very first trio.”

After spending a fruitful ten months with Miles Davis in 1958, which produced, among other things, the classic LP Kind Of Blue (about which Evans nonchalantly remarks, “We just really went in that day and did our thing”), Bill Evans started in the trio setting that would soon be the prototype for dozens of piano/bass/drum combos.

“When I first started the trio after leaving Miles, I started with Jimmy Garrison and Kenny Dennis. We were working at Basin St. East opposite Benny Goodman, who was making sort of a triumphal return, and we were treated so shabbily — they would turn the mikes off on us, et cetera, et cetera. They were giving Benny’s band state dinners with champagne and we couldn’t get a coke without paying two bucks and getting it ourselves. Anyhow, the guys’ egos couldn't take it. Kenny Dennis and Jimmy Garrison left very shortly. The gig was two or three weeks and I think I went through four drummers and seven bass players during that gig.

"Philly Joe was on that gig for a little while and we really started cooking. We started getting some applause and then they told me not to let Joe take any more solos. I said, 'Well, I’m not going to tell him. If you want to tell Philly Joe Jones he can’t solo, you tell him.’ That’s the way it was.

“Scott LaFaro was working around the corner on a duo job and he came over to sit in a couple of times. Paul Motian, who I had been friendly with, I knew had been busy. By the end of the gig both of those guys were available and interested and that’s who I ended up with. They became the original trio and it was the right original trio. So sometimes those situations maybe are karmic or in some way fated, so that you eliminate the people that aren’t committed and perhaps even aren’t right, and end up with the right thing.”

Bill Evans alternates his free time between a small apartment in New Jersey and a home in Connecticut. The New Jersey apartment, where he sits in work shirt and jeans, contains mostly a Chickering baby grand piano, with a book of Bach fugues open on the stand, and various reminders of his phenomenal recording career— including most of the albums under his own name and five dusty Grammy awards. It seems that Bill Evans has always been recording and his output, on Riverside, Verve, Fantasy, Columbia and, currently, Warner Bros., remains extremely popular. The Bill Evans bins in the jazz sections of record stores are always brimming.

"I’ve been going through a period recently — I hadn’t listened to my own music for years and years. I often made records and didn’t hear them. Recently I’ve been going back and studying my recorded output and I find some things that sound better than I thought and some things that don’t sound as good. Of course I have almost 50 LPs now under my own name out, so there’s some dead wood as far as I’m concerned.

“The first album under my name was a trio album (New Jazz Conception), Riverside 12-223), but it wasn’t a set, developing group. It was a nice record, though: Teddy Kotick on bass and Paul Motian on drums. This was late ’55. The second record was also a trio record, but again not a set trio, with Philly Joe Jones and Sam Jones.

“Following that I started recording with Scott and Paul. We hadn't worked too much before the first record — about four weeks at a little place called the Showplace in Greenwich Village. That gave us some basis to record. The second album was a bit more developed and then, of course, the last night we played together before Scott was killed represents the two albums live from the Village Vanguard." (Bill Evans/The Village Vanguard Sessions, Milestone 47002).

LaFaro died several weeks later in a car accident, at the age of 25. But the pattern was set — Evans has never stopped working in a trio setting featuring a strong bassist. Through the mid '60s it was usually Chuck Israels; in 1966 Evans found Eddie Gomez at the Village Vanguard.

“He was working with Gerry Mulligan. I was looking for both a drummer and a bass player at the time and Eddie just impressed the hell out of me. I asked him if he would be interested.”

He was, and the gig lasted 11 years. Their playing together was often astonishing. Gomez developed into a superlative soloist and together he and Evans recorded and performed prolifically. During that time Bill Evans worked on expanding his lyrical approach, by experimenting with the electric piano and overdubbing several layers of his own improvisations, which he first did in 1963 with Conversations With Myself (Verve 68526) and has most recently done on the brittle and brilliant New Conversations (Warner Bros. BSK 3177) done in 1977.

With Marty Morell as drummer from 1968-1975, the Bill Evans Trio played straight ahead romantic jazz through jazz’s worst years. “Although the late ’60s were lean years for jazz, I always managed to keep working and recording.”

When many musicians began playing the electric pianos that started springing up about ten years ago, their playing changed drastically. Evans, on the other hand, has always remained himself and his work on the Fender Rhodes is unmistakably his own. Yet he is not satisfied enough with the instrument to use it often in performance.

“The acoustic piano still represents, far and away, the superior medium for me to express myself. I have tried various electric pianos and I have an Omni synthesizer, but I’m not attracted to them. I don’t really consider it in any way a complete instrument. It has nothing like the depth and the scope of an acoustic piano. I don’t think that anybody who has any understanding would argue that point. It does have an attractive sound and in certain contexts it is very effective with the kind of articulation and sound that it gets.

“I approach the Rhodes with my own touch and my own feeling for sound and articulation and it probably results in putting some kind of identity into the Rhodes. I don’t do anything really that different. The rental Rhodes that they send out for record dates are beat up and noisy—the pedals are noisy.

“In fact we had a hell of a time trying to find one. I went to the leading instrument rental place in New York, went upstairs to where they had the Rhodes and I must have tried every one, I think they had 18 or 20 of them there, and not one was satisfactory. Not one! They were all beat up. It’s okay for a rock date where you have an awful lot of sound going and like that, but the action was all screwed up, the sound was uneven. Or it would be squeaky or noisy or whatever. I suggested to this instrument rental place that they keep at least one for pianists who want to do more sensitive things, but they didn’t go for the idea. I don’t know why. They lost the rental for a week, which I think probably would have paid the price of the piano.”

If Bill Evans is anything, it’s constant. Besides not changing his musical approach over the last quarter century, he’s had the same manager. Helen Keane, for 18 years and has considered the Village Vanguard his New York home for that time. He does his auditions there, records there and plays there at least three or four times a year. “I just feel completely at home at that club. It’s a good club for listening; it’s a good club for feeling close to the people. Max Gordon [the owner of the club] and I are good friends. There was a time when the original trio was more or less the house trio. We played opposite a lot of people and I’m sure we worked there maybe weeks a year for a couple of years.

“Max has created an atmosphere of relaxation. Musicians can drop in and out to say hello. It’s not a stiff policy where you have to get a pass to get in. It's congenial in that respect, and I think it has a lot to do with the good vibes that happen in the club. I hope the club goes on forever and ever. They even have the same tables and chairs. I worked there first in '55 and nothing’s changed. The only thing that’s changed is they put some stuff on the walls.”

If the Village Vanguard has been a home for Bill Evans, certainly no record company has offered that comfort. Although he hasn’t been without a contract since his first LP, Evans has passed through at least five companies since that time. Most recently he switched from Fantasy to Warner Bros., a company which is just beginning to test the waters of improvisatory music. “Fantasy was a nice, congenial atmosphere and. of course, they had all my old Riverside catalog as well. I’ve known and loved Orrin Keepnews for many years but. frankly, the production budget isn’t there. If you want to do a larger thing, it’s hard to get it done. Basic money isn’t there for recording and I just got a vastly better contract at Warner Bros. They wanted to start a jazz catalog and I was more or less the start."

While Evans keeps only a trio together for performing, his recordings in the ’70s have featured him in many different contexts: two albums with Tony Bennett, the Quintessence LP with Harold Land and Kenny Burrell, Crosscurrents with Lee Konitz and Warne Marsh, and the recent Affinity with Toots Thielemans and Larry Schneider. His next album to be recorded will feature a quintet with Tom Harrell's trumpet and Schneider’s tenor sax. When I first listened to Affinity I was very impressed with Schneider’s long, tough tenor lines.

"Oh, he's just marvelous. I had heard him play a ballad called Yours And Mine with the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Band three years ago in Tulsa and I was so impressed that two and a half years later I told Helen to try and locate him. It was a matter, again, of a musician impressing himself upon me to that point.”

But despite his admiration for Schneider, Bill Evans has no plans to enlarge the group.

"I like to play with horns occasionally. As far as my ideal playing setting, where I can shape the music and control the music more, the trio is a pure kind of group. As long as I can get by successfully, careerwise, with a trio, it’s my ideal thing. It’s the thing I aimed for way before I could get a trio off the ground. It's the thing I wanted. I enjoy playing with horns, but it changes the whole approach to the

music because the horns become the primary voice in a sense. It just changes everything.

“I would like someday to play more solo. I don’t feel I have a great scope or dimension as a solo pianist because I’ve never really worked as a solo pianist. But I do like to play solo. It's kind of a special feeling of communion and meditation that you can't get any other way.”

One of the things that Bill Evans was never lacking was an audience. Now that audience seems to be increasing in size and decreasing in age.

"It’s encouraging — the audiences are getting larger and they’re mostly young people. Eighty percent of our audiences are young people, the kind of young people that ten years ago wouldn’t have been aware of jazz at all. I don't know the reasons for it especially, but there's a larger group of discriminating young people who are getting very involved in jazz and are getting interested in the whole history of jazz as well.

“I think they’re interested in the genuine article, whether it’s avant garde or whether it’s traditional or whatever. Perhaps jazz has come of age in that respect. Like classical music, it has a history now that’s sufficient and available. So a real dedicated fan can study the history of jazz, and learn to appreciate jazz from the beginning to the present.

“This seems to be something I notice more about the new young fans, whereas when I was coming up everybody was only interested in what was happening then, right on the forefront. You wouldn’t listen to dixieland and you wouldn’t listen to swing unless you were coming up in that period. But I see where a lot of young people now will go back and listen to a lot of historical things.”

One of the consequences of this ever searching young audience is that a lot of them are picking up reissues and then coming into the clubs and asking Bill Evans to play some barely remembered tunes.

“Yeah, that can happen, especially when you change personnel. With Eddie Gomez I could reach back and pull things out blind that he would know, but it’s a little more limited when you change personnel. I get a lot of requests for Peace Piece which I never have played. I only did it that once, which is on the record. If I can answer a request I’m very happy to do it."

As Bill Evans speaks his eyes dart around the floor. He is thinner than he has been and his beard looks a little longer. Every so often he lets a short Elmer Fudd-ish laugh escape and a quick smile makes its way across the serious face, like when I ask if he’s ever considered changing his name to Yusef Lateef. Yusef's real name is . . . William Evans.

“Not too many people know about that. I’m sure glad he changed it, though. It certainly would have been a nuisance.”

The smile, I realize, is a rarity. Of his entire recorded oeuvre I can’t think of a single cover in which the spectacled, professorial Evans is smiling.

“It gets a little over-emphasized and so, naturally, they just choose pictures like that. If there are four pictures and I’m smiling on two, they pick the one with the serious look. People tend to pigeonhole everything. My image seems to be of the intellectual, serious, romantic, lyric, ballad player and this is certainly one side of myself. But I think I put much more effort, study and development and intensity into just straight ahead jazz playing, the language of it and all that — swinging, energy, whatever. It seems that people don’t dwell on that aspect of my playing very much; it’s almost always the romantic, lyric thing, which is fine, but I really like to think of myself as a more total jazz player than that.”

In order to pose for several photographs the intellectual, serious, romantic, lyric, ballad player sits himself at his Chickering and begins to spin magnificent variations of the old chestnut I Fall In Love Too Easily. Behind him sits a bookcase filled with albums by himself, Jackie and Roy, Rachmaninoff, Cecil Taylor, Aaron Copland and a predominance of LPs by the likes of Steve Martin, Lord Buckley, Albert Brooks and Richard Pryor. Bill Evans, in his 50th year and his 25th year as a professional jazz pianist, quietly enters a new phase of his life.

“I suppose we go through periods and I feel that I’m more outgoing. The last year or so I especially feel like I’ve been coming into a period of greater expressivity — more outgoing with a little more emotional scope and a little more projection. It's just a natural thing, but I think it's a period I’m coming into.”

SELECTED BILL EVANS DISCOGRAPHY

SINCE WE MET—Fantasy F9501

ALONE—Verve V6-8792

SPRING LEAVES—Milestone M47034

MONTREUX III—Fantasy F9510

THE SECOND TRIO—Milestone M47046

TRIO—Verve VE2 2509

INTUITION—Fantasy F9475

QUINTESSENCE—Fantasy F9529

PEACE PIECE AND OTHER PIECES—Milestone M47829

NEW CONVERSATIONS—Warner Bros. BSK 3177

AFFINITY—Warner Bros. BSK 3293

BILL EVANS ALBUM/TIME—Columbia C33672

with Miles Davis KIND OF BLUE—Columbia CS8163

I have a daughter named Emily. Listening to Bill play that song is pure joy.

A great piece. Thank you for bringing it back.